“I was made for this.”

— Lee Harker

Something happens in Longlegs that doesn’t happen in most horror movies.

You don’t walk out asking, what did I just see?

You walk out asking, why did that feel like something I already knew?

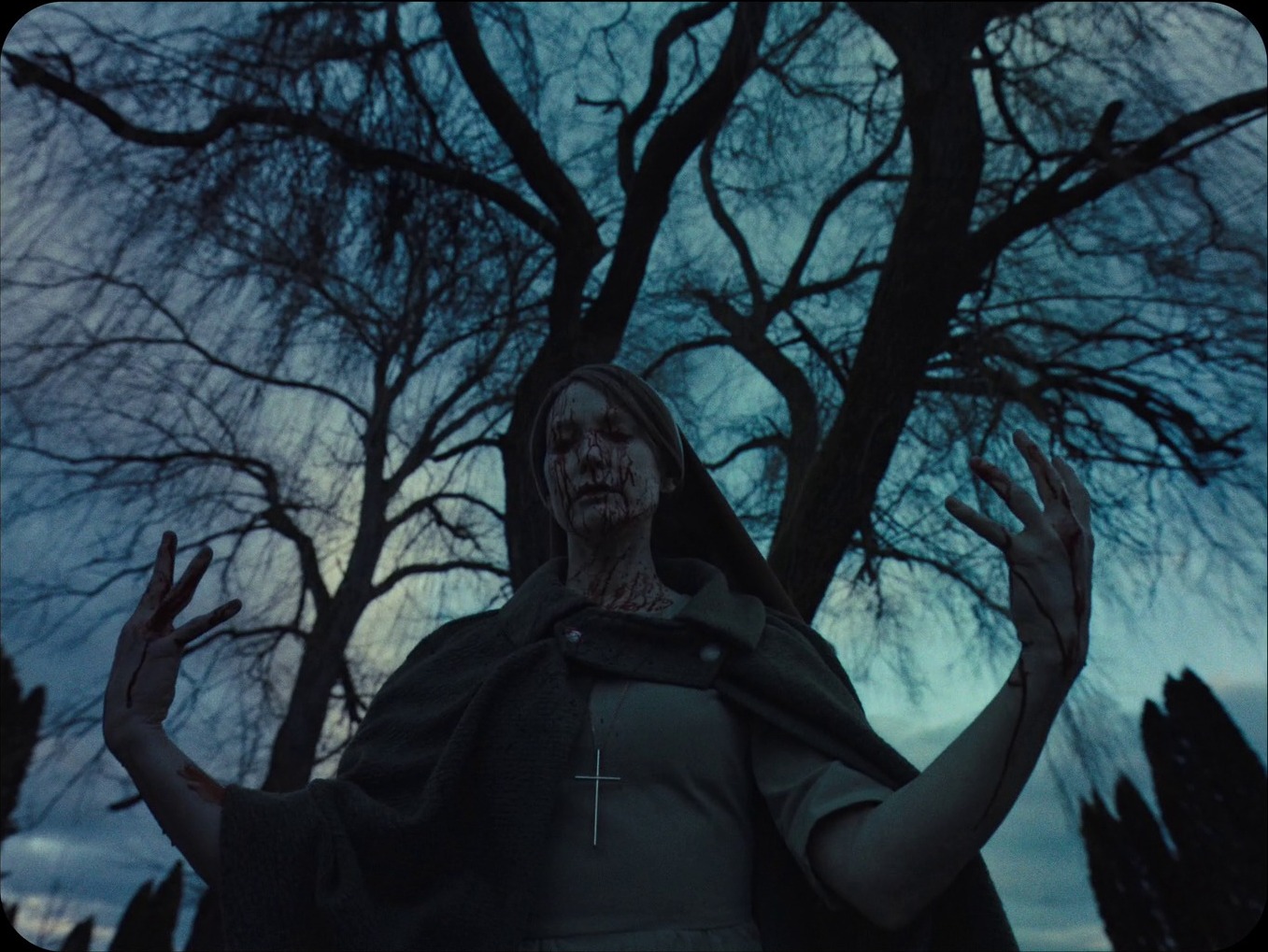

Osgood Perkins’ 2024 nightmare is about a serial killer, sure. But Longlegs isn’t about who the killer is. It’s not even about how to stop him. It’s about why it hurts so much to look your own trauma in the face, and why that trauma, when you finally name it, looks exactly like the very person that raised you.

Let’s talk about the psychological layers beneath Longlegs. And not the “it’s about grief” surface reading. We’re going deeper. Into repression. Guilt. The trauma of being born to a woman who didn’t want you, and the unbearable truth of being just like her.

The Serial Killer as a Symptom, Not a Monster

Longlegs (played by Nicolas Cage in one of the most uncomfortably incorrect performances of the decade) is not your villain. He’s your diagnosis. He’s a thing that was made. Warped. Bent backwards into religious delusion, self mutilation, and occult mania, but all of it in service to something else. Something beneath. That “something else” is motherhood. Specifically, the nightmare of being raised by a woman who hated herself and passed that hatred down like DNA. And the fear of becoming that woman, of inheriting not just her genetics, but her damage. The real horror of Longlegs isn’t Satan. It’s the knowledge that cycles of violence and repression start at home. And they do not end with a bullet.

Lee Harker and the Repression Reflex

Lee (Maika Monroe) is the kind of character that psychology textbooks love to use as case studies. Emotionally numb. Dissociative. Deeply intuitive but profoundly closed off. A walking example of what psychoanalyst Alice Miller called “the gifted child,” the child who learns to survive not by being themselves, but by sensing what others want and becoming that. Lee is quiet not because she’s stoic. She’s quiet because her brain has been compartmentalizing since birth. And in that quiet is a rage she doesn’t understand. Her investigation isn’t really about Longlegs. It’s about recovering repressed memories. When she uncovers the pattern of mother-daughter killings, she’s not solving a mystery, she’s waking up to the truth of herself. Her own mother is part of it. She was always part of it. And Lee knows, on some buried level, that she’s not just chasing a killer, she’s chasing origin. And that’s what terrifies her more than any crime scene.

The Face of the Devil is Maternal

In Longlegs, Satan is real. Or at least real enough to be believed in. But the Devil’s actual power in the movie doesn’t come from black magic or demonic possession. It comes from parenting. Longlegs becomes what he is because of what his mother taught him, not just consciously, but preverbally, through how she saw him. Through how she ignored him. Through how she punished or neglected or smothered him. When he mutilates his own face to please the Devil, he’s really trying to please his mother. But here’s the twist: that’s also what Lee is doing. There’s a recurring pattern in the film: children trying to escape their parents, only to become them. Longlegs is a product of that pattern. Lee is its consequence. The Devil is just a metaphor for the thing that shaped them both. And his face, distorted, uncanny, inhuman, is the psychological mirror of the mother who breaks her child long before language can form.

The Scariest Thing: Inherited Evil

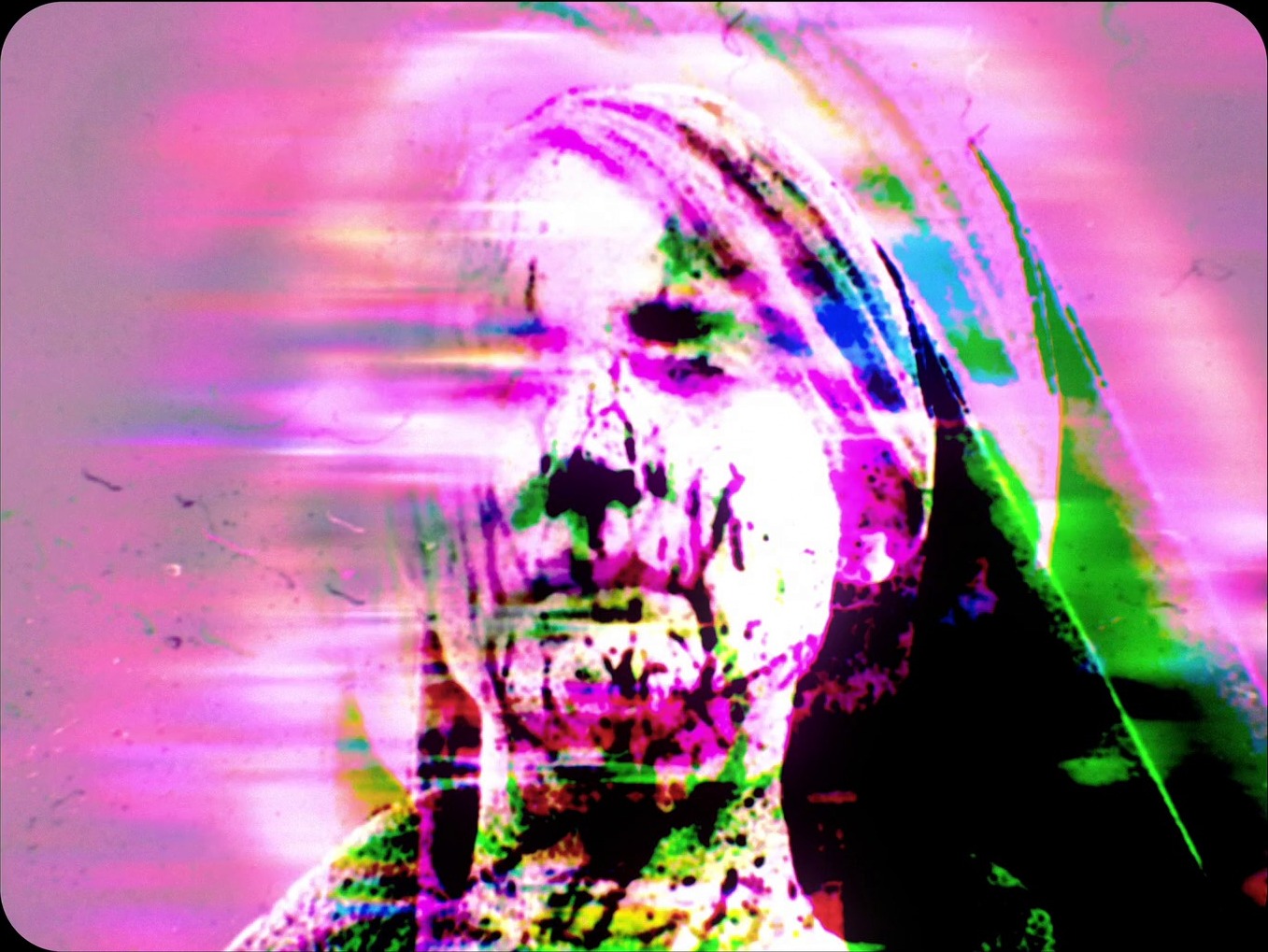

There’s a moment in the film, no spoilers, where Lee realizes she’s not an exception. Not above it. Not different. Just another echo of the same trauma. And that’s when Longlegs gets its fangs in. Because we, the audience, want her to be the hero. The one who breaks the cycle. But the movie doesn’t let her have that clean of a victory. Because it’s not about victory. It’s about recognition.

Recognition that evil doesn’t always feel evil.

Sometimes it feels like silence. Or guilt. Or the ache of needing your mother and resenting her at the same time.

Sometimes it feels like you.

Why This Hurts More Than It Should

So why does Longlegs stick to your bones?

Not just because it’s scary. It IS scary. But that’s not why.

It sticks because it makes you confront the part of you that wants to believe your pain is unique. That you’re different from the people who hurt you.

But what if you’re not?

What if you’re them, just with a better haircut, a badge, and the illusion of moral clarity?

That’s Longlegs at its most brutal.

It turns the mirror inward. And it whispers, “You were made for this.”

Longlegs is a movie about the emotional DNA of trauma.

About how childhood doesn’t end when you grow up.

About how evil isn’t some outsider. It’s homegrown. Handed down like a family heirloom.

And if that didn’t haunt you, you weren’t really watching the movie.