When people talk about animated horror, they usually name Coraline or maybe Perfect Blue if they wanna sound clever. But somewhere out there, crawling in the dusty forgotten corners of the genre, is The Apostle (2012). A Spanish animated film directed by Fernando Cortizo, The Apostle is a slow, methodical study of how guilt, isolation, and religious obsession rot the human soul like black mold growing under a pristine white wall. And yeah, it’s stop motion animation, but don’t let that fool you. This isn’t cozy Tim Burton territory. The Apostle feels like being trapped inside a church that’s been abandoned by both God and people, listening to your own breathing while the walls drip memories you wish you could erase.

But let’s not just call it “creepy” and be done. The Apostle is a movie about very real psychological horrors. Let’s talk about it.

Guilt as a Parasite

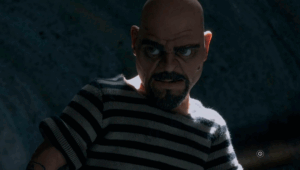

The story kicks off with an escaped convict, Ramón, running from the law, but mostly running from his past. His mission. Retrieve stolen treasure from an old village. A simple plot, but The Apostle doesn’t care about big twists. It cares about the inside of Ramón’s mind, and how guilt doesn’t just sit quietly in the background. It festers. It mutates. Psychologically, guilt acts almost exactly like a parasite. It doesn’t kill you right away. It burrows into your decisions, your dreams, even your basic ability to trust the world around you. Ramón is already carrying that parasite when he steps into the village, and what he finds there, the villagers already corrupted by their own secrets, the priest bound by unspoken sins, mirrors what’s already happening inside him. The scary part isn’t that the village is haunted. It’s that Ramón is haunted, and the village simply gives shape to what’s already rotting him from the inside.

The Psychology of Isolation

There’s a clinical term psychologists use called “social death.” It’s when someone is still technically alive but has been cut off from meaningful human interaction so long that mentally, emotionally, they’re already dead. Isolation is more deadly than most trauma because it doesn’t even need an event. It’s a slow bleed of meaning. In The Apostle, every single character feels socially dead. The villagers mutter to themselves, hiding behind rituals that no longer connect them to anything divine. The old priest seems like he’s just a shadow pretending to still be human. Even the landscapes, the fog, the endless woods, make it feel like Ramón is traveling not into a place, but deeper into a state of mental collapse. Real isolation doesn’t feel like a screaming horror movie chase scene. It feels like what this movie shows: cold, slow, sinking into yourself until you can’t tell memory from dream.

Religious Delusion and “The God-Shaped Hole”

Religion in The Apostle isn’t about faith. It’s about powerlessness. The villagers’ religious rituals are empty performances. There’s no salvation coming, and they know it. But they keep praying because not praying would mean admitting the truth; that they’re alone. Completely and forever. Psychologists talk about the “God-shaped hole.” This idea that humans are born with a deep need for meaning and connection, and if we don’t find it through spirituality or community, the hole gets filled with fear, guilt, obsession, whatever else we can grab. In The Apostle, that hole is gaping wide. The villagers’ prayers aren’t acts of faith. They’re acts of fear. They’re desperately trying to patch over an existential void they know, deep down, can’t ever really be filled. Ramón, meanwhile, isn’t religious, but that doesn’t save him either. His treasure hunt is its own twisted ritual. His belief that he can “fix” things by claiming the treasure is just as delusional as the villagers’ candlelit prayers. It’s two sides of the same broken human need to control the uncontrollable.

Why The Animation Style Matters

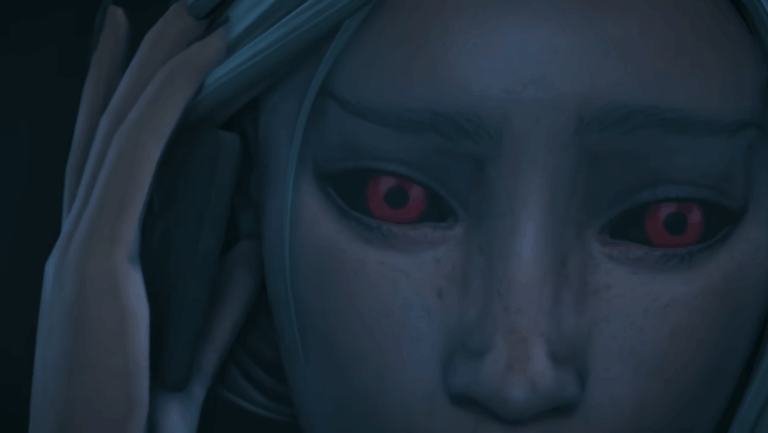

If The Apostle had been live action, it would’ve still been bleak. But the stop-motion animation creates a creepier feel, and it’s not just about aesthetics. Stop motion is inherently unnatural. Movements are jerky. Faces are stiff. There’s always something subtly “off,” even when it’s done perfectly. And here, Cortizo leans into that offness. The characters’ stiff smiles, their heavy lidded eyes, they don’t look alive. They look like people who forgot how to be people. Psychologically, this taps into what’s called the “uncanny valley” effect, when something looks almost human but not quite, it triggers a primal discomfort. It’s our brains’ way of screaming something is wrong here. In The Apostle, every frame pushes you deeper into that uncanny valley. It’s like watching a dream where the people you love have been replaced with hollow puppets that just pretend to know you.

Death Isn’t Scary. Meaninglessness Is.

If you really zoom out, The Apostle isn’t about fear of death. Death is practically a release for most of these characters. What’s truly terrifying is the idea that your suffering has no point. That the rituals, the regrets, the prayers, the betrayals. They didn’t add up to anything. This is existential horror at its purest. There’s no big monster behind the curtain, no evil spirit pulling the strings. There’s just human nature, eating itself alive. The real nightmare of The Apostle is realizing that redemption might not exist. That guilt can’t be scrubbed clean. That even if you do everything “right,” it doesn’t guarantee any kind of peace. That sometimes you’re just… lost. Forever.

The Apostle Is About You (Whether You Like It or Not)

Maybe that’s why The Apostle didn’t blow up when it came out. It’s not a movie that lets you walk away feeling good about yourself. It’s not full of jump scares and gore. It’s a slow, smothering mirror. It forces you to sit with questions you’d rather leave in the dark:

- What sins are you pretending aren’t sins?

- What rituals are you still performing, even though deep down you know they don’t work?

- When was the last time you felt truly connected to anything or anyone?

In the end, The Apostle isn’t just about an escaped convict and a cursed village. It’s about the small, invisible ways we rot ourselves from the inside out, through guilt, loneliness, desperation, and the unbearable, aching hunger for meaning that might never come. And that’s scarier than any ghost story.