There are breakups, and then there is Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981). This is a raw, screaming, utterly unhinged psychoanalysis of a relationship decomposing into grotesque body horror, existential dread, and a terrifying descent into madness.

For the connoisseurs of true psychological extremity, this is a film that doesn’t just depict a nervous breakdown; it feels like one you’re experiencing alongside its doomed protagonists, caught in a suffocating web of paranoia and primal terror.

Set against the stark, oppressive backdrop of Cold War-era West Berlin, the film plunges us immediately into the marital maelstrom of Anna (Isabelle Adjani) and Mark (Sam Neill). He returns from a mysterious espionage mission to find her distant, erratic, and demanding a divorce. Their initial confrontations are not arguments; they are operatic explosions of accusations, despair, and a terrifying inability to communicate. Żuławski’s camera, frantic and intrusive, mirrors their fractured psyches, trapping us in their claustrophobic, spiraling hysteria.

The core horror of Possession lies in its relentless ambiguity. Anna’s increasingly bizarre behavior—her secret apartment, her mysterious lover, her inexplicable fits of violence and unsettling calm—drives Mark to obsessive paranoia. Is she having an affair? Is she mentally ill? Or is something far more monstrous at play? The film never fully clarifies, instead forcing the audience to inhabit Mark’s agonizing uncertainty, making his descent into madness almost inevitable. His increasingly desperate attempts to control Anna, to understand her, only push her further into her own terrifying reality.

Isabelle Adjani’s performance is a masterclass in visceral terror, particularly in the infamous subway tunnel miscarriage scene. This sequence is not just body horror; it’s the raw, unadulterated manifestation of psychological torment externalized. Her convulsive thrashing, vomiting, and screaming aren’t just physical; they’re the ultimate expression of a mind and body being ripped apart by unspeakable forces, whether internal or external. It’s a moment so grotesque and profoundly disturbing that it imprints itself on the viewer’s psyche.

As the film progresses, the nature of Anna’s “lover” is revealed: a slimy, tentacled, otherworldly creature that she keeps hidden in her apartment. This creature is the ultimate embodiment of their relationship’s decay – a monstrous offspring born of their mutual hatred, fear, and shattered intimacy. It’s a physical manifestation of everything dark and unspeakable that has festered between them. The creature literally consumes, growing stronger as their love, and their sanity, waste away.

Possession explores profound psychological themes: the breakdown of identity in the face of profound relational trauma, the inherent violence within human connection, and the terrifying fluidity of reality when sanity fractures. The appearance of doppelgängers – Anna’s eerie double, Helen (also Adjani), and Mark’s violent, unhinged counterpart – further blurs the lines. These doubles are not just spooky coincidences; they are psychological projections, reflections of fragmented selves, perhaps even alternative realities where the characters seek escape or embody their repressed desires. They symbolize the terrifying notion that in such extreme distress, the self can splinter, producing monstrous versions of who we once were, or who we truly are beneath the surface.

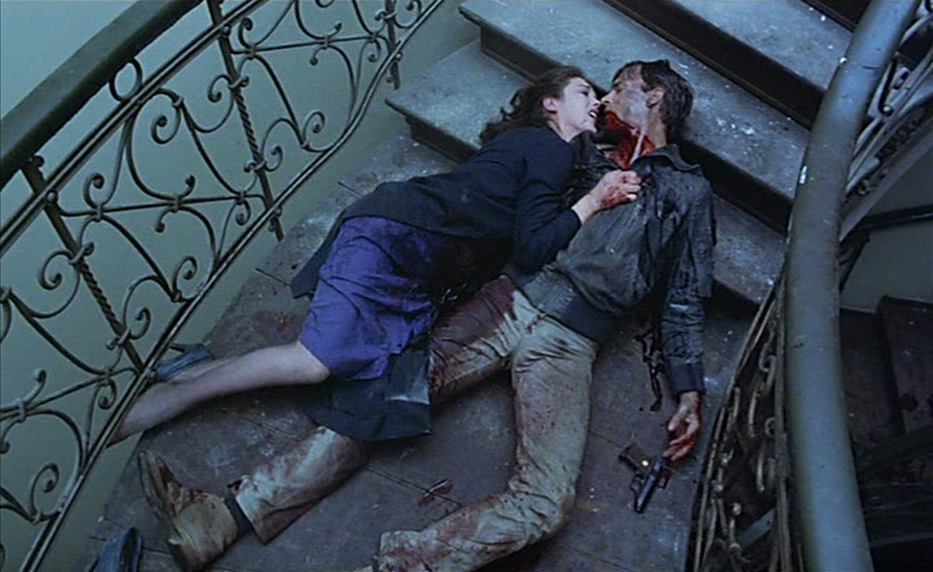

The final act is a hallucinatory, apocalyptic ballet of self-destruction. As the creature grows, their world descends into utter chaos, culminating in a grotesque, violent climax that leaves both Mark and Anna consumed by their monstrous creation. The ending, with the child, Bob, encountering his own doppelgänger and the chilling sound of sirens, suggests a cyclical, inescapable horror. The trauma is inherited, the madness perpetuated, an endless loop of breakdown and rebirth into something equally terrifying.

Possession is not just a film you watch; it’s a film you endure. It’s a raw, bleeding wound of a movie that forces us to confront the monstrousness that can arise from within, particularly when love turns to venom and the foundations of reality crumble. It’s a terrifying testament to the idea that sometimes, the greatest horrors are not supernatural invaders, but the unspeakable truths we unleash when our hearts, and our minds, are pushed beyond the brink.