There are monsters under the bed, and then there are monsters in bespoke suits, impeccably groomed, dissecting album reviews while contemplating unspeakable acts.

Mary Harron’s 2000 adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho is not merely a horror film; it’s a surgical, unsettling psychoanalysis of narcissism, consumerism, and the terrifying elasticity of reality in a society utterly devoid of genuine connection. For the audience of horrorpsych.us, this is a deep dive into the mind of a predator where the line between fantasy and atrocity is perpetually, horrifyingly blurred.

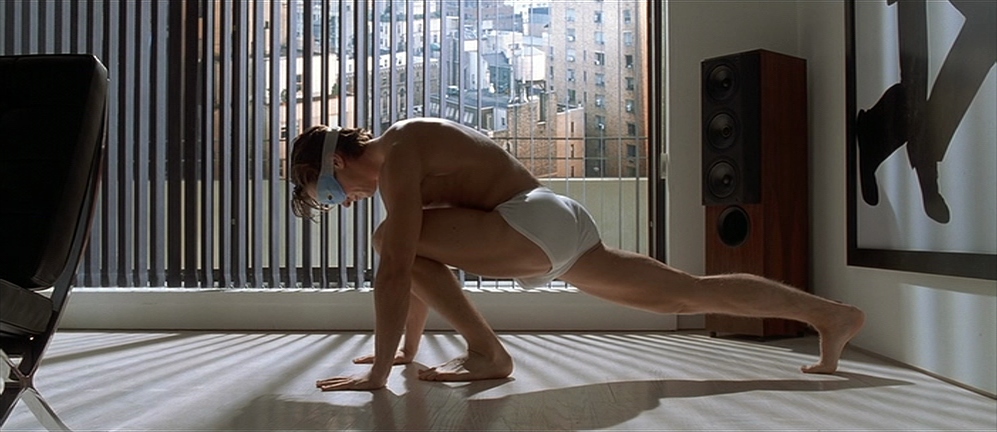

We are introduced to Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale), a young, impossibly wealthy Wall Street investment banker in late 1980s New York. His world is a meticulously ordered universe of designer labels, exclusive restaurants, and a relentless pursuit of superficial perfection. Every detail, from his morning routine of elaborate skincare to his obsession with the raised lettering on a business card, is a desperate attempt to construct an identity in a world where everyone is indistinguishable. This isn’t just vanity; it’s a profound, pathological need for control and validation, a fragile facade barely containing the chaos within.

The core horror of American Psycho lies in its ambiguity. Did Patrick Bateman truly commit the heinous murders, rapes, and tortures he so graphically describes? Or are these lurid fantasies, the grotesque manifestations of a deeply disturbed mind struggling to find meaning and individuality in a soulless, hyper-materialistic world? Harron, much like Ellis, masterfully maintains this uncertainty, forcing the audience into a chilling complicity, left to ponder the true nature of the violence. This unreliability of the narrator is the film’s most potent psychological weapon.

Bateman’s psychopathy is a fascinating case study. He exhibits classic traits of Antisocial Personality Disorder and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: a profound lack of empathy, grandiosity, superficial charm, and a chilling disregard for societal norms. His detached narrations, often shifting seamlessly from an obsessive critique of pop music to a methodical description of torture, highlight his emotional void. He knows the societal rules but feels no compunction to follow them, viewing others as mere objects for his fleeting pleasure or grotesque amusement.

The film serves as a brutal satire of 1980s corporate culture and the dehumanizing effects of rampant consumerism. Bateman and his peers are interchangeable clones, obsessed with status symbols, often mistaking each other for someone else. This social blindness is crucial: it allows Bateman to operate with impunity. People are so self-absorbed, so consumed by their own shallow pursuits, that they literally cannot see the monster in their midst. The indifference of those around him, whether it’s his detached fiancée Evelyn (Reese Witherspoon) or his oblivious lawyer, is arguably more terrifying than Bateman’s own violence. Their lack of acknowledgment effectively traps Bateman in his own personal hell, where even confessing his crimes offers no release.

The violence, whether real or imagined, is symbolic. It’s the desperate attempt of an utterly alienated individual to feel something, to make an impact, to distinguish himself in a world that has rendered him invisible despite his wealth and privilege. The graphic nature of the murders, especially those against women, also serves as a stark critique of misogyny and the objectification rampant in his social sphere. Women are reduced to commodities, interchangeable bodies to be used and discarded, mirroring the disposable nature of luxury goods.

American Psycho is a chilling reflection, holding a mirror up to the darkest corners of capitalist excess and the human psyche. It probes the terrifying question: what happens when a society values appearance over substance, wealth over humanity, and ego over empathy? Bateman’s final monologue, lamenting his lack of punishment and his inability to escape his own internal torment, is a profound statement on the hell of an unexamined life, trapped in an endless cycle of gratification and depravity. It suggests that the true “American Psycho” might not just be one man, but the very system that created him, nurturing his void until it screams.