“You must think me a very sinister doctor… Oh, I do have the simplest explanation. I met him, fifteen years ago; I was told there was nothing left. No reason, no conscience, no understanding, and even the most rudimentary sense of life or death, good or evil, right or wrong…” – Dr. Sam Loomis

In 1978, John Carpenter unleashed Halloween onto an unassuming world—cheaply made, tightly scripted, and unknowingly immortal. But this was no monster movie. There were no vampires, werewolves, or cosmic threats. Instead, Carpenter gave us The Shape. Blank-faced. Silent. Methodical. A killer without appetite, rage, or motive. And that is precisely what made him terrifying.

At the center of Halloween lies a psychological enigma: Michael Myers. Not a man, not even a monster—an absence. In that void, we find the core of the film’s genius: a relentless, unsettling meditation on evil as something unknowable. Halloween is not about what Michael does—it’s about what he doesn’t do. He doesn’t talk. He doesn’t react. He doesn’t stop.

THE CHILD WHO STOPPED BEING HUMAN

Michael is introduced in the film’s shocking cold open: a six-year-old child stabbing his sister to death. We see it through his eyes—an unbroken POV shot that Carpenter forces us to endure in real-time. It’s not just a stylistic choice; it’s a statement. We are Michael. The audience is lured into complicity before they’ve even met Laurie Strode.

But there’s no pleasure in the kill. No frenzy. It’s banal. Silent. Void of meaning. And that, perhaps, is Carpenter’s cruelest trick. In most slashers, there’s an explanation. A traumatic backstory. A revenge plot. With Michael, there’s no key to the lock. No trauma, no abuse, no triggers. Only the horrifying suggestion that sometimes, evil just is.

THE SHAPE AND THE SHADOW

Dr. Loomis’ psychological analysis of Michael has become as iconic as the film itself. “This isn’t a man,” he insists, again and again. What makes Loomis a tragic figure isn’t that he wants to stop Michael—it’s that he’s already lost. He knows Michael is beyond comprehension, yet he keeps trying to explain him. Loomis becomes a symbol of the rational mind collapsing in the face of pure, unfiltered chaos.

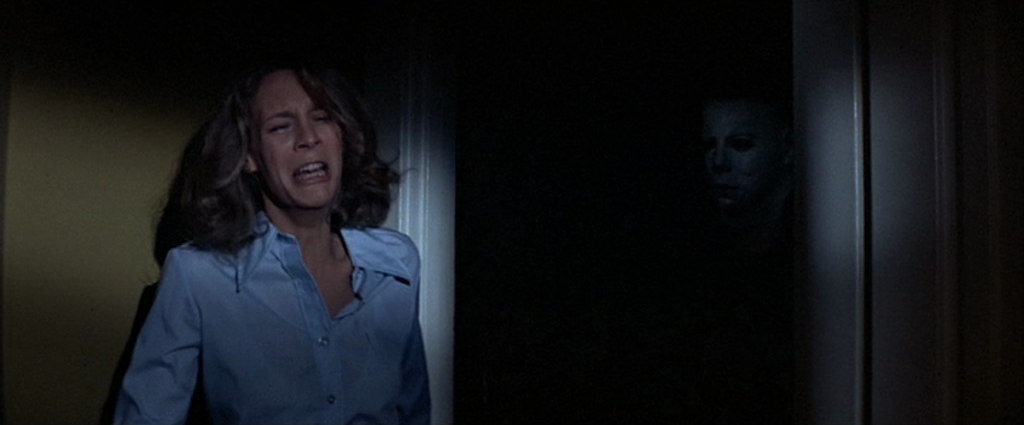

Carpenter strips Michael of humanity through every frame. He doesn’t run—he glides. He doesn’t speak—he breathes. He doesn’t reveal himself—he lurks. The mask becomes essential to this dissociation. Michael is no longer a person in disguise; the disguise is the person. He is “The Shape,” credited as such in the original script. A Jungian shadow—everything we repress, everything we deny, everything we fear might be true about ourselves.

SUBURBIA AS SLAUGHTERHOUSE

Set in the fictional town of Haddonfield, Halloween is built on a lie: the American suburb as sanctuary. Laurie Strode and her friends move through a world of beige walls, cul-de-sacs, and neatly trimmed hedges. But the longer we watch, the more the setting feels like a dream that’s rotting from the inside. This is a landscape of repression. Teenagers babysit and flirt and joke about sex, but the air is thick with dread. There are no parents around. The authority figures are absent or incompetent. The phone lines cut. The lights too dim.

Michael doesn’t break into their world—he was always there. Watching. Waiting. Like a virus dormant in the bloodstream.

THE FINAL GIRL AND THE VIRGIN SACRIFICE

Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) is frequently reduced to a trope in horror analysis: the Final Girl. But Carpenter’s treatment of her is more nuanced. Laurie is not a virgin because the script moralizes sex; she’s a virgin because she is disconnected. Withdrawn. Watching the world from the outside. Like Michael, in a sense. Both are isolated observers—but where Michael is consumed by absence, Laurie is defined by empathy.

Her strength is not physical—it’s psychological. She adapts. She problem-solves. She survives not by fighting like a slasher heroine of the ’80s, but by enduring. Yet even her survival is laced with trauma. By the end, she’s sobbing, shaking, a wide-eyed child in an adult’s body. The final shot, where Michael has vanished after being shot six times, is not triumphant—it’s damning. Evil is not dead. It was never alive to begin with.

THE PSYCHOPATH WITH NO MOTIVE

Modern horror films often fall into the trap of over-explanation. They tell us why the killer kills, so we can sleep at night believing there was a cause. But Carpenter understood that true terror lies in the senseless. Michael is the walking void. No cause, no cure. He is a psychopath without psychosis. He doesn’t hallucinate. He isn’t tormented. He simply kills.

This idea taps into a deep psychological terror: the realization that not all behavior can be rationalized. That some evil is immune to analysis. Carpenter’s genius was refusing to give us anything solid to hold onto. He makes us stare into the abyss, and when we blink, it’s already inside the house.

HALLOWEEN AS EXISTENTIAL HORROR

Halloween (1978) is often credited as the genesis of the slasher genre—but its heart beats like existential horror. It confronts us not just with death, but with meaninglessness. Michael Myers is not a person, not a metaphor, not even a ghost. He’s a psychological event. A question with no answer. The idea that sometimes, evil doesn’t knock—it waits, patiently, breathing behind a closet door.

And that’s what makes Halloween timeless. Not the knife. Not the mask. But the silence.