It isn’t the ghosts that truly haunt you. Not initially, anyway. It’s the vast, suffocating emptiness. The impossible architecture. The relentless, creeping sense of being utterly, irrevocably alone with your own demons.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) doesn’t exactly tell a ghost story; it invites you into a meticulously constructed psychological torture chamber, a sprawling canvas where the thin veneer of sanity cracks and peels under the pressure of isolation, ambition, and a deeply inherited rot. For the discerning eye of horrorpsych.us, this is less a film to be watched and more a waking nightmare to be experienced.

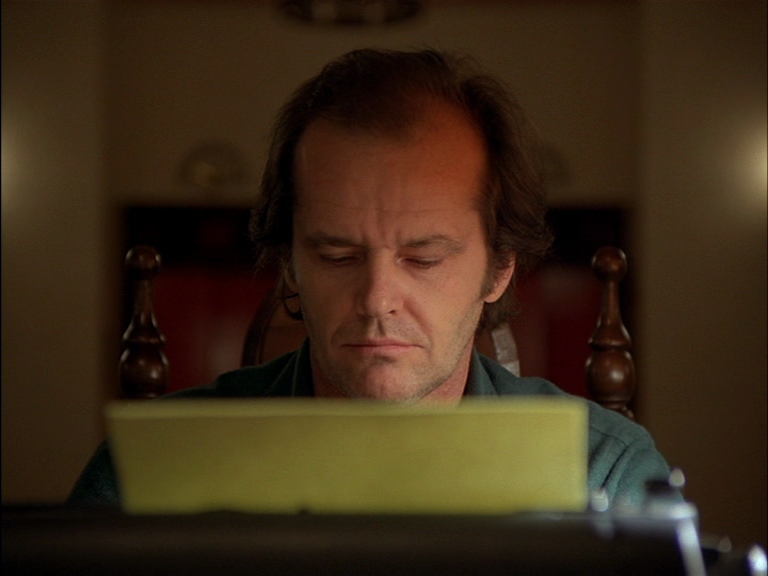

Consider Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson), the aspiring writer and recovering alcoholic, who takes on the winter caretaker position at the isolated Overlook Hotel. He seeks quiet, inspiration, a fresh start. What he finds, or perhaps what finds him, is an amplifying chamber for his own simmering rage and insidious vulnerabilities. The hotel itself is not merely a setting; it’s a colossal, malignant entity, a psychic sponge soaking up decades of violence, depravity, and unspoken horrors. It breathes. It watches. And it demands.

The true terror lies in the slow, agonizing erosion of Jack’s already fragile psyche. His descent into madness isn’t sudden. It’s a meticulously paced unraveling, marked by increasingly erratic behavior, disturbing visions, and a chilling detachment from his family. Is it the hotel’s malevolent influence? Or is the Overlook simply stripping away the carefully constructed facade of a man already predisposed to violence, a man whose darkest impulses were merely waiting for the perfect, isolated environment to bloom? The film deliberately leaves this ambiguous, making the horror all the more potent.

And then there’s Wendy Torrance (Shelley Duvall), the often-maligned figure of the long-suffering wife. Her terror is palpable, a constant state of wide-eyed, desperate apprehension. She is the witness, the victim, trapped in a horrifying domestic drama where her husband transforms before her eyes into a homicidal monster. Her journey is one of pure, unrelenting survival, a testament to the primal fear of being utterly at the mercy of someone you once loved, now consumed by an unknowable evil. Her screams, her tears, her desperate fight – they are the raw, human counterpoint to Jack’s theatrical madness, grounding the supernatural in visceral dread.

Young Danny Torrance (Danny Lloyd), with his preternatural “shining” ability, serves as the conduit to the hotel’s dark past and its malevolent intentions. He sees the atrocities that unfolded, hears the whispers of the dead, and warns of the impending doom. His terror is profound, often expressed with an unnerving calm that makes it all the more chilling. He is the innocent caught in the crossfire of adult pathologies and spectral malevolence, his psychic gifts a terrifying burden rather than a protective shield.

Kubrick’s mastery lies in his control of space and perception. The Overlook’s impossible layout, its endless hallways, its disorienting symmetry – it all serves to disorient the audience, mirroring Jack’s own fracturing reality. The long, tracking shots follow Danny’s tricycle, creating a sense of inescapable dread, an inexorable movement towards an unseen horror. The iconic imagery—the blood pouring from the elevator, the Grady twins, the woman in Room 237—they are not just startling visuals, but psychological implants, designed to burrow into the subconscious and fester.

The Shining peels back the layers of the American family unit, exposing the toxic masculinity, the inherited trauma, and the claustrophobic pressures that can lead to destruction. It suggests that the monsters are not always supernatural entities, but the very real demons of alcoholism, repressed violence, and the desperate yearning for a false sense of control. The hotel merely provides the stage, the echo chamber, for these deeply human horrors to play out.

In the end, Jack’s pursuit of Danny through the snow-filled maze is not just a physical chase; it’s a chilling metaphor for the inescapable nature of one’s own darkest impulses. And the final, haunting photograph – Jack in 1921, forever part of the Overlook – cements the terrifying idea that some spirits are not external entities, but the enduring, inescapable manifestations of a deeply fractured, eternally repeating cycle of violence. The Shining remains a chilling, profound psychoanalysis of madness, an inescapable mirror held up to the darkest corners of the human heart, trapped forever in the cold, vast emptiness of a very long winter.