The quiet can be deafening. The stillness, a suffocating weight. And sometimes, the very air in an empty apartment can become an accomplice to madness.

Roman Polanski’s 1965 masterpiece, Repulsion, doesn’t just depict psychosis; it invites you to crawl inside it, to feel the cold, clammy tendrils of a fragile mind shattering, piece by agonizing piece. This isn’t horror for the jump-scare crowd; this is a deeply unsettling, almost unbearable psychoanalysis experienced from the inside out, a meticulous charting of a soul’s descent into a terrifying, visceral abyss. For the discerning eye of horrorpsych.us, Repulsion remains the quintessential nightmare of the interior.

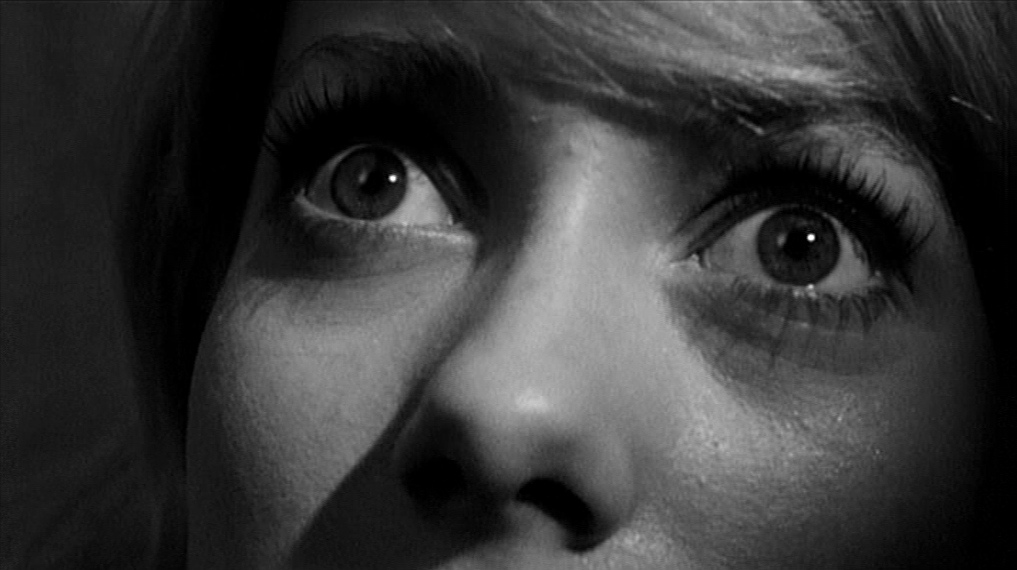

Meet Carol Ledoux (Catherine Deneuve), a breathtakingly beautiful Belgian émigré working as a manicurist in London. On the surface, she’s serene, almost angelic. But beneath that porcelain exterior, a terrifying fragility lurks. She’s repulsed by the tactile world, particularly by men and anything remotely sexual. A touch makes her flinch; a casual flirtation sends shivers of revulsion through her. Her discomfort is palpable, a constant hum of barely contained anxiety that Polanski establishes with unnerving subtlety. Her sister, Helen, provides the only tether to a semblance of normality, often playing the role of protector against the clumsy advances of men and the pressures of the outside world.

When Helen leaves for a vacation with her married lover, Carol is left alone in their shared apartment. And the walls begin to whisper.

This is where the film truly becomes a psychological gauntlet. Polanski doesn’t rely on ghosts or monsters; the horror is born entirely from Carol’s disintegrating mind. The apartment, once a haven, transforms into a terrifying prison. The mundane becomes menacing: a raw rabbit carcass left on the counter, slowly putrefying; a persistent, dripping faucet that sounds like a hammer striking ice; cracks appearing on the walls, bleeding into her vision, mirroring the fissures in her own psyche. These aren’t just symbols; they are extensions of her internal collapse, materialized anxieties reaching out to grasp her.

The intrusions are subtle at first, then increasingly aggressive. Shadows stretch and distort. Hands reach out from the walls. Menacing figures appear in her peripheral vision. The film’s brilliant sound design becomes a sensory assault – the clock ticking, the neighbor’s arguments, the incessant noise outside – all magnified, distorted, and utterly overwhelming to Carol’s hypersensitive state. She is experiencing sensory overload, her mind unable to filter, categorize, or contextualize the onslaught.

What drives this terrifying breakdown? The film offers clues, but no easy answers. A deeply repressed trauma? A burgeoning schizophrenia? A profound fear of male sexuality and the physical body itself? Her revulsion is visceral, absolute. When the well-meaning Colin attempts to force his affections on her, her reaction is swift, brutal, and horrifying. Her violence is not premeditated; it’s a panicked, animalistic lashing out, a desperate attempt to fend off an perceived invasion that exists both externally and, perhaps more terrifyingly, within her own burgeoning sexuality.

Carol’s murders are an act of self-preservation in her distorted reality. Each victim represents an intrusion, a violation, a threat to her increasingly fragile inner world. The bathtub sequence, with its grotesque details, is not just a moment of horror; it’s a testament to a mind losing all grasp on consequence, on reality, on the sanctity of human life. She is becoming a predator, not out of malice, but out of a profound, deranged fear, a complete inability to differentiate between threat and normalcy.

Repulsion is a masterclass in subjective horror. We don’t just see Carol’s world; we feel it. We experience her escalating paranoia, her hallucinations, her physical and mental decay. Polanski forces us into her isolated, terrified state, where the mundane becomes monstrous and the familiar transforms into something utterly alien. The final image, a chilling photograph from her childhood, hints at a past trauma, a seed planted long ago that has finally blossomed into this terrifying, beautiful, and ultimately devastating madness.

This is a film that lingers, not in memory, but in the unsettling feeling of the world shifting just beyond the edge of your perception, a terrifying reminder that the greatest horrors are sometimes locked away, not in a dark room, but in the fragile confines of our own minds.