Darren Aronofsky’s 2010 masterpiece, Black Swan, is not just a psychological thriller; it’s a visceral, unflinching dissection of a soul tearing itself apart in the crucible of artistic obsession.

For Horror Psych readers, this is horror of the most insidious kind: the terror that blooms from within, transforming ambition into madness and self-discovery into self-destruction.

At the heart of this nightmare is Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman), a ballerina of extraordinary talent but crippling innocence. She is the quintessential “White Swan” – pure, precise, technically flawless. But the demanding artistic director, Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel), sees her potential for the “Black Swan” – the seductive, uninhibited counterpart that requires a raw, dangerous sensuality Nina utterly lacks. This dual role isn’t just a physical challenge; it’s a psychological gauntlet designed to shatter her fragile psyche.

Nina’s life is a suffocating cocoon woven by her overbearing mother, Erica (Barbara Hershey), a former ballerina whose own dreams were thwarted. Erica’s presence is less maternal and more parasitic, feeding off Nina’s ambition while simultaneously stifling her growth. Nina’s bedroom, still adorned with childhood paraphernalia, is a visual metaphor for her arrested development. This claustrophobic environment is the perfect breeding ground for the horrors that begin to manifest.

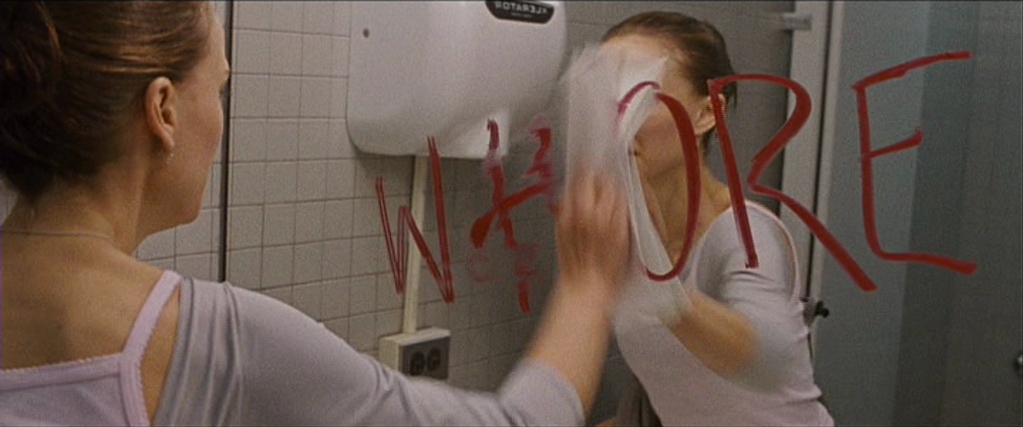

As Nina strives to embody the Black Swan, the film relentlessly blurs the lines between reality and hallucination. The cracks in her sanity appear subtly at first: a phantom scratch on her back, a doppelgänger glimpse in her reflection, the chilling animation of her mother’s artwork. These aren’t just jump scares; they are the insidious whispers of a mind unraveling, unable to reconcile the rigid purity she’s been taught with the dark, sexual awakening demanded by her art.

The arrival of Lily (Mila Kunis), the free-spirited, effortlessly sensual new dancer, acts as both catalyst and tormentor. Lily is everything Nina isn’t – uninhibited, confident, effortlessly embodying the very essence of the Black Swan. Nina’s burgeoning obsession with Lily morphs into a terrifying doppelgänger complex, where attraction and repulsion, admiration and resentment, become indistinguishable. Is Lily a real rival, a figment of Nina’s psychosis, or a terrifying projection of Nina’s own repressed desires? Aronofsky brilliantly keeps us guessing, pulling us deeper into Nina’s unreliable perception.

The true horror of Black Swan is its exploration of perfectionism as a self-devouring beast. Nina’s relentless pursuit of flawlessness becomes a form of self-mutilation. Her physical body, the instrument of her art, becomes a canvas for her psychological torment: peeling skin, festering wounds, the grotesque transformation of her feet. The ballet world, seemingly so elegant, is revealed as a brutal, cutthroat arena where dancers are pushed to the brink, sacrificing their bodies and minds for an elusive ideal.

The film’s climax is a breathtaking, tragic ballet of madness. As Nina performs the Black Swan, she transcends. But this transcendence is born from a horrific delusion, a final, fatal embrace of her dark half that culminates in self-inflicted violence. Her declaration, “I felt it… I was perfect,” as she bleeds out on stage, is the ultimate, chilling punchline. Perfection, in this nightmare, is death. It’s the ultimate sacrifice, not just of her body, but of any hope for a unified, sane self.

Black Swan is a harrowing journey into the depths of artistic obsession and psychological disintegration. It’s a warning about the crushing weight of expectation, the insidious nature of unresolved trauma, and the terrifying price of shedding one’s innocence for an ideal that may only exist in the mind. It’s a film that leaves you with the lingering image of a beautiful, broken creature, dancing her way into oblivion, a masterpiece of horror born from the very soul of ambition.